“A lot of people tell me, ‘It must have been so great to be a Ripken.’ And I go, ‘Well, I’m proud to be a Ripken, but not for the reasons you might think.’ ” – Ryan Ripken

When Cal Ripken Jr. gets together with his son, Ryan, they rekindle their rivalry.

“He never let me win when I was a kid,” says Ryan Ripken, Cal’s 30-year-old son. “And I’m glad. I tell you what, though, when I started beating him at basketball, that was fun.”

The two once had a competition going at cribbage on a flight back to the states from South Africa. Ryan won the cards marathon but his dad wanted to continue the game on their connecting flight.

“I’ll play with you, but this doesn’t count,” Ryan said he told his father. “He ended up winning the two games on the flight. And he’s like, ‘Champion.’ ”

Follow every MLB game: Latest MLB scores, stats, schedules and standings.

Some would say there’s a Ripken Way to playing baseball. It’s about work and careful dedication to a craft until you excel at it, and until you are a stronger person for it.

It’s about fathers and sons sharing the game together but also loving something, and those around you who believe in your cause, so much that you dedicate your life to it.

And it’s about not letting your kid win.

“I can wholeheartedly say we hated losing,” Ryan says. “Especially as we got older.”

Cal Ripken’s baseball life, and the pains and competitive spirit it took to excel at it, created a movement of fans who have thanked him over the years, sometimes tearfully, for what his enduring Hall of Fame career has meant to their lives. Today, fathers and sons come to his Ripken Baseball complexes, which host youth tournaments but also promote the lessons of his father, Cal Sr.

Twenty-three-years removed from his retirement, Ripken has followed his father’s lead as a baseball lifer and coach into a second baseball career.

After an injury derailed his chance of reaching the major leagues, Cal Sr. dedicated his life to helping young players in the Baltimore Orioles system try to fulfill their own dream of getting there. Along the way, he set a standard for workmanship and services that his family follows.

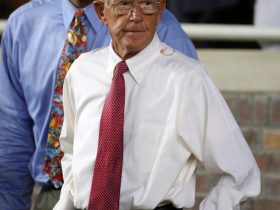

“I’ve learned that you put in your time, work really hard, you have the power in your own work that can make you better and give you a chance,” Cal Jr., 63, told USA TODAY Sports at last month’s Project Play Summit in Baltimore.

On Father’s Day, let’s look at how the Ripken Way can help you and your young athlete chase dreams, but also keep you grounded.

1. ‘You can observe a lot by watching’

Like Yogi Berra, another proud baseball dad who is credited with that saying, Cal Jr. learned baseball inside and out by watching. More specifically, he and his three siblings watched their dad.

Whether it was edging his driveway with two nails, a string and a hatchet, or hitting ground balls to players, there was an earnestness Cal Sr. lived by that became a guidepost for his son’s record streak 2,632 consecutive games.

Cal could also see a healthy mix of humanity in it all as a bat boy during his childhood summers. He watched how his father asked a pitcher to chart games and mark players’ mistakes with a red dot by their names. The dots became index cards his father created to remember the situations.

But they never became heat-of-the-moment exchanges. The next day, Cal Sr. casually called the player into his office, looked at him with his deep blue eyes and went over the mistake. He offered a small compliment when he was finished. I love how you’re swinging the bat, keep going.

“The guy who walked out of the room like 30 seconds later, his chest would be all up, he’d be all happy,” Cal Jr. recalled. “If you tried to do that during the course of the game, they’re already upset they made a mistake and they would fight you a little bit, and then nothing would get done.”

Years later, when he helped coach Ryan’s Little League team, Cal watched other coaches scream out to his son’s teammates during games. Cal marked his observations in a notebook.

“Don’t yell out,” he told the other coaches. “Just write it down. And then we’ll figure it out together. You don’t want to embarrass them. You want to explain what happens because kids are really sensitive to that.”

Cal Sr. didn’t know he was giving lessons. He was just being himself and living his life. It’s a reminder how we are always on display for our kids, showing off the best – or worst – we have to offer.

“I never saw my dad be upset with any outcome of the game,” says Ryan Ripken, who played in the minors for seven years and is now a sports media personality in Baltimore. “The biggest thing was, ‘Are you giving your effort? Are you working hard? And if you’re doing those things, we can work on the other stuff.”

Coach Steve: What sons of famous MLB players can teach sports parents

2. ‘Figure out who you are’

There is at least one outcome that brightens Cal Ripken’s day. It occurs when working with a kid, perhaps an at-risk kid through the foundation he and his family created in his father’s name, and you ‘hook’ them.

Imagine you’re teaching someone hitting for the first time, but you realize he is athletic and brimming with potential. You notice he’s holding the bat too high on the handle or cross-handed, so you make the slight adjustment.

“All of a sudden … POW! … The ball comes off his bat, the eyes light up,” says Ripken, his own deep blue eyes widening. “Now you’ve kind of hooked him, and now you can kind of guide them.

‘We’ve used baseball as the icebreaker or sports as the icebreaker. And then once you create a trusting relationship through mentorships, and those sorts of things, then you can help guide the kids in other ways as well.”

When kids are having fun with their sports, as Cal did playing baseball, basketball and soccer when he was a boy, they don’t even realize the lessons they are learning.

Ripken says if he had the ability to make one thing happen all across youth sports, it would be to remove the pressure we put on kids during games. His advice: At an early age, expose them to different sports and see which ones makes them most happy. When they find the game they love, you both will know.

It’s the way Cal and Kelly Ripken, Ryan’s mother, allowed their kids to grow through their sports and activities.

“My family would have loved me if I’d never ever picked up a baseball once in my life,” Ryan says. “There was never pressure to do it. I almost chose playing basketball, but I could never put down the glove or the bat. [It was] something deep inside of me that I wanted to do, not that I was being pushed by my family members at all.”

Coach Steve: What makes pickleball the perfect sport for everybody

3. ‘You are guaranteed to fail’ and it’s never as bad as you think

When Ryan reached Class AAA ball, the minor leagues’ highest rung, he still felt the weight of his family name. But he remembers Cal Sr.’s example: Sometimes the pursuit of a goal, and what you do after you don’t achieve it, is more worthwhile.

As he got older, Ryan began to work with kids, too, at camps and clinics. Like his grandfather, he has thought about how to help kids beyond each specific game so they can understand themselves better.

“Who helps you when you’re in there?” he has asked kids when they are hitting. Some tell him it’s that coach who’s yelling at them. Others realize they’re in the batter’s box doing the work by themselves.

“I will always be here to help you, but my goal is, ‘How can you figure out who you are?’ ” he tells them. “And in the process of working that style, I think they learn how to deal with failures themselves.”

Yes, his dad was physically talented, a seemingly overgrown shortstop who made things look so easy. But he was also someone who seemed to change his stance dozens of times during his 21-year professional career. He was trying to find a feel, a comfort level with himself in a game of ups and downs.

“He always had frustrations just like everyone else did,” Ryan said. “But how do you learn to leave what had happened in the past behind?”

Cal Sr. managed the Orioles for just over two seasons. He was fired after the team began its infamous 1988 season 0-6. It would go on to start 0-21. Cal Jr. said the experience taught him not to run away from a challenge but to try and figure out how to solve it.

Its’s that mental makeup, learning how to move past failure, Ryan says, that set his dad apart. We can’t be Cal Ripken, but we can teach our kids that even when we lose, or when we strike out, there is still a lesson. Each instance as an opportunity.

“How many times did I worry about failing and worry about, ‘What if something goes wrong?’” Ryan says. “I think for me that opened up my mind of, ‘Life’s hard enough. Things are hard, but every bad moment’s gonna pass.’ And that was something I wished as a kid I understood. It’s never as bad as it seems. And don’t let your fear of someone else stop you from doing what you love to do.

“I think kids compare themselves and worry about so many other things besides you get to be with friends, you get to learn a game that you love.”

4. It’s OK to lose sometimes. It doesn’t mean you are giving in.

Let’s go back to a game when Ryan was 8. The opposing coach was playing to win. You’ve likely seen the scenario before. The Ripken team’s pitcher wasn’t throwing strikes, and every time he tossed another ball, that coach would yell to his hitter, “Make sure he throws a strike!”

Ryan’s teammate walked the bases loaded, throwing wild pitch after wild pitch. Parents from the other team cheered, clapped and high-fived. The pitcher cried.

As the moment was unfolding, Cal Jr. thought to himself: We’ll get through this.

“If you wanted to win at 8 years old, tell your kids to take until they get to two strikes, don’t swing the bat at all. They’ll walk you. Then they’ll run around the bases, and then you’ll win the game,’ he says. ‘But you haven’t learned how to hit. You haven’t learned how to field.

“Sometimes we as parents get a little bit into the game, and we press and our competitive nature comes out and we want to win, win, win. My advice would be take a step back, realize the bigger picture, be a little bit more patient, let them develop and to try to alleviate pressure.”

Ripken called over the other coach. Even the dad who doesn’t let his son win knows when to tap the breaks.

‘We forfeit,’ he said. ‘So now let’s just play a practice game.”

Steve Borelli, aka Coach Steve, has been an editor and writer with USA TODAY since 1999. He spent 10 years coaching his two sons’ baseball and basketball teams. He and his wife, Colleen, are now sports parents for a high schooler and middle schooler. His column is posted weekly. For his past columns, click here.